Professor Edwards republication of various essays of mine concerned with theological subjects is a cause of gratitude to me, especially in view of his admirable prefatory observations. I am particularly glad that this opportunity has occurred for reaffirming my conviction on the subjects with which the various essays deal.

There has been a rumor in recent year to the effect that I have become less opposed to religious orthodoxy than I formerly was. This rumor is totally without foundation. I think all the great religions of the world - Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, and communism - both untrue and harmful. It is evident as a matter of logic that, since they disagree, not more than one of them can be true. With very few exceptions, the religion which a man accepts is that of the community in which he lives, which makes it obvious that the influence of environment is what has led him to accept the religion in question. It is true that the Scholastics invented what professed to be logical arguments proving the existence of God, and that these arguments proving the existence of God, and that these arguments, or others of a similar tenor, have been accepted by many eminent philosophers, but the logic to which these traditional arguments appealed is of an antiquated Aristotelian sort which is now rejected by practically all logicians except such as are Catholics. There is one of these arguments which is not purely logical. I mean the argument from design, this argument, however was destroyed by Darwin; and, in any case, could only be made logically respectable at the cost of abandoning God's omnipotence. Apart from logical cogency, there is to me something a little odd about the ethical valuations of those who think that an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent Deity, after preparing the ground by many millions of years of lifeless nebulae, would consider Himself adequately rewarded by the final emergence of Hitler and Stalin and the H-bomb.

There has been a rumor in recent year to the effect that I have become less opposed to religious orthodoxy than I formerly was. This rumor is totally without foundation. I think all the great religions of the world - Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, and communism - both untrue and harmful. It is evident as a matter of logic that, since they disagree, not more than one of them can be true. With very few exceptions, the religion which a man accepts is that of the community in which he lives, which makes it obvious that the influence of environment is what has led him to accept the religion in question. It is true that the Scholastics invented what professed to be logical arguments proving the existence of God, and that these arguments proving the existence of God, and that these arguments, or others of a similar tenor, have been accepted by many eminent philosophers, but the logic to which these traditional arguments appealed is of an antiquated Aristotelian sort which is now rejected by practically all logicians except such as are Catholics. There is one of these arguments which is not purely logical. I mean the argument from design, this argument, however was destroyed by Darwin; and, in any case, could only be made logically respectable at the cost of abandoning God's omnipotence. Apart from logical cogency, there is to me something a little odd about the ethical valuations of those who think that an omnipotent, omniscient, and benevolent Deity, after preparing the ground by many millions of years of lifeless nebulae, would consider Himself adequately rewarded by the final emergence of Hitler and Stalin and the H-bomb.

The question of the truth of a religion is one thing, but the question of its usefulness is another. I am as firmly convinced that religions do harm as I am that they are untrue.

The harm that is done by a religion is of two sorts, the one depending on the kind of belief which it is thought ought to be given to it, and the other upon the particular tenets believed. As regards the kind of belief: it is virtuous to have faith -- that is to say, to have a conviction which cannot be shaken by contrary evidence. Or, if contrary evidence must be suppressed. On such grounds, the young are not allowed to hear arguments, in Russian, in favor of capitalism, or in America, in favor of Communism. This keeps the faith of both intact and ready for internecine war. The conviction that it is important to believe this or that, even if a free inquiry would not support the belief, is one which is common to almost all religions, and which inspires all systems of state education the consequence is that the minds of the young are stunted and are filled with fanatical hostility both to those who have other fanaticisms and, even more virulently, to those who object to all fanaticisms. A habit of basing convictions upon evidence, and of giving to them only that degree of certainty which the evidence warrants, would, if it became general, cure most of the ills from which the world is suffering. But at present, in most countries, education aims at preventing the growth of such a habit, and men who refuse to profess belief in some system of unfounded dogmas are not considered suitable as teachers of the young.

The above evils are independent of the particular creed in question and exist equally, in all creeds which are held dogmatically. But they are also, in most religions, specific ethical tenets which do definite harm. The Catholic condemnation of birth control, if it could prevail, would make the mitigation of poverty and the abolition of war impossible. The Hindu beliefs that the cow is a sacred animal and that it is wicked for widows to remarry cause quite needless suffering. The Communist belief in the dictatorship of a minority of True Believers has produced a whole crop of abominations.

We are sometimes told that only fanaticism can make a social group effective. I think this is totally contrary to the lessons of history. But, in any case, only those who slavishly worship success can think that effectiveness is admirable without regard to what is effected. For my part, I think it be better to do a little good than to do much harm. The world that I should wish to see would be one freed from the virulence of group hostilities and capable of realizing that happiness for all is to be derived rather from co-operation than from strife. I should wish to see a world in which education aimed at mental freedom rather than at imprisoning the minds of the young in a rigid armor of dogma calculated to protect them through life against the shafts of impartial evidence. The world needs open hearts and open minds, and it is not through rigid systems, whether old or new, that these can be derived.

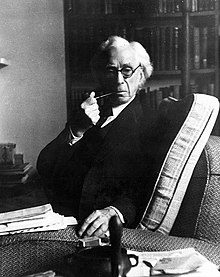

Bertrand Russel 1957

Bertrand Russel Why I am not a Christian

< - - - - - - - -- - - - - - - - - - >

Questions:

1. How can there be good and evil

2. When did Darwinian view of Evolution become a fact rather than a theory?

3. Did he really believe the absence of religion is really an neutral position not a new religion of Self?

4. The world does need open minds and hearts but need you through out the baby to get them? Is he not stating that no one except those who think like him have an open heart and mind, and is it not rather close minded to think that way?